- Home

- Caitlin Vance

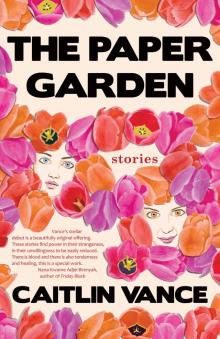

The Paper Garden

The Paper Garden Read online

PRAISE FOR

THE PAPER GARDEN

“Vance’s stories, at their best, are immersive and gripping.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Vance’s stellar debut is a beautiful original offering. These stories find power in their strangeness, in their unwillingness to be easily reduced. There is blood and there is also tenderness and healing, this is a special work.”

—Nana Kwama Adjei-Brenyah, author of Friday Black

“I loved Caitlin Vance’s debut collection of stories and fractured fairy tales for its sensibility, which is simultaneously strange, angry, funny, tender, and wisely (and wryly) perceptive. Her characters (so often abandoned by parents or struggling with unreliable partners or the mentally ill) are compelling in their survival strategies. Without being Pollyanna—or slipping too wholly into the ever-present darkness of the world—they come out on top simply by making it to the end of their own remarkable stories.”

—Debra Spark, author of The Pretty Girl

“These haunting and hilarious tales expose the fissures, absurdities, and inconsistencies in the stories we’re told and the stories we tell ourselves. Whether the subject is an old parable, the haunted home of a troubled couple, the digressive answers penned into an intake form by a woman anxiously awaiting treatment, Vance’s strange and often brutal worlds are signed with human, horror, and beauty.”

—Jessica Alexander, author of Dear Enemy

the Paper garden

_

stories by

Caitlin Vance

7.13 Books

Brooklyn

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

This book is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real places are used fictitiously. Other names, characters, places, and events are products of the author’s imagination, and any resemblance to actual events or places or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Selections of up to one page may be reproduced without permission. To reproduce more than one page of any one portion of this book, write to 7.13 Books at [email protected].

Cover art by Gigi Little

Edited by Hasanthika Sirisena

Copyright ©2021 by Caitlin Vance

ISBN (paperback): 978-1-7361767-0-2

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-7361767-1-9

Library of Congress Control Number (LCCN): 2020953031

tulips | 1

a red winter shadow | 19

the miraculous pregnant virgin | 35

the house| 53

doctor's office paperwork | 57

i can tell what's real and what's pretend | 65

pheromones | 83

my life is the size of a walnut | 95

the hills | 109

sleepwalking | 115

the paper garden | 137

snowflake | 151

tulips

The house across the street was dark. It looked as if it had burned down and someone had re-built it using ash and tar and human bones. Small pieces of wood crumbled off it like Play-Doh, and windows were cracked. The grass was too tall, so that you had to look very closely to see the small garden of flowers bordering the house. I was six years old and I thought all the spiders in the world must hide there in winter. I thought there must be demons inside, plotting with maps and charts to trick people into coming in. For those first few days after my mother and I had moved in with my grandma in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho from across town, I watched the house, waiting to see a candle flicker or a hand drag across a window, but there was nothing.

On a summer evening not long after we moved to Grandma’s, the sun hummed over the Earth’s surface, so that there was a pressure, little hands pushing everything down, little bees filling space with white noise. The whole world felt tired and the sun scorched the ends of my hair, turning it to straw. I sat in the gravel of the front yard petting our cat, watching the house. A car pulled up after days of no sign of life; a man and a woman stepped out of it. The man went inside right away while the woman stayed, fiddling with things in the back seat. She was wearing a long dress like a river. Her hair was brown like mine, and braided, longer than any hair I’d ever seen. When she spotted me from across the street, she smiled the way I might smile if I’d finally made it to Disneyland. A cavity in my chest filled quickly with warm liquid. She picked up a paper grocery bag with something shiny sticking out of it, and came to me.

“Hello,” she said, glowing.

I thought of a dream I’d had: I was in bed and couldn’t speak or move. I stared up at the woman.

“What a pretty girl you are,” she said, digging in her paper bag and pulling out the shiny thing, which was a necklace with a huge cross on the end. “I’ve just come from a church conference. The pastor gave everyone one of these to hang around their necks. It’s nice to have God’s love so close to your heart.” She touched her own cross, which hung exactly at her heart and caught the sun, so that the orange of it stung right into my eyes. “I have one left over, but no daughter of my own to give it to. You look like you might like it.” She hung the extra necklace over me. “My name’s Scarlett and that man is my husband, Daniel.” She pointed behind her at the house. “Do you have a name?”

I kept looking at her heart. The necklace was heavy, and I was small, and the cross hung closer to my belly button than my heart. “Saige,” I said, so quietly she must have barely been able to hear me over the sound of a bouncing basketball up the street.

Scarlett went back to her house and I sat in the yard, thinking about this cross around my neck, about whether I should tear it off and bury it in the gravel, whether it was evil and Scarlett was evil and something in that house wanted me doomed. But I also thought maybe Scarlett had fallen into this house accidentally, that she didn’t know it was evil, and that she was even sent here by God to save it. The way she spoke to me, her voice soft like petals, and the way she gave me this necklace, made me want to believe in her. The sun hung lower and I went inside.

I found my mother where I often found her that summer: in her rocking chair near the window, just looking out. She was wrapped in an afghan she had made back when she did things like that, back when she did anything at all. My mother was twenty-three. My best friend in first grade, Abigail, had a sister who was twenty-two. My mother was thin all over and had dusty hair she kept tied up with an old ribbon. She wore dresses in different shades of brown, like paper bags holding the sticks of her body together.

My father had left her a few months before I met Scarlett for the first time. He simply told my mother there was someone else and drove off. She hadn’t told me yet, but kept saying he was away on business. My father was a trucker. I knew he wasn’t coming back, because his trips never lasted as long as two months, and besides, I’d overheard my mother telling my grandma about it. Still, I imagined him driving along the coast, watching seagulls fly and waves crash out the window all the way to California. I’d never been to the ocean. I didn’t know how to tell my mother I thought she was a liar.

Shortly after my father left, my grandmother showed up at our apartment with a U-Haul and a bundle of trash bags. She said it was time for an intervention, and when I asked what that meant, she said my mother just needed a little help right now, that’s all. My mother sat in her rocking chair without a word while Grandma carefully inspected each item in the apartment, scrunched her nose, and scrubbed the item with a rag before cramming it into the truck.

When my parents were together, my father worked and my mother stayed at home taking care of me. A lot of mothers in Coeur d’Alene di

d this; childcare was too expensive to make having a job worth it. My mother dropped out of high school to give birth to me, the baby she’d conceived in the backseat of a blue Toyota with one brown door. When my father was actually away on business, things were different. My mother taught me to bake all kinds of cookies, draw bubble letters, and play “Happy Birthday” on the keyboard. She gave me a special Bible for kids and read to me while I sat on her lap, examining the patterns in her afghans and knitted scarves.

“Mom, I met a new lady,” I said to my rocking mother. “She lives in the scary house. Is she bad? She gave me a necklace.” I held it up for her to inspect. I knew she’d seen the whole thing out the window.

“How should I know?” she asked. She went to the kitchen and pulled a can of tomato soup out of the cupboard. “Saige,” she said, “Come help me stir the soup for dinner.”

Even though she didn’t do much else that summer, my mother still tucked me into bed and sang to me each night. She had a beautiful singing voice, better than anyone’s at church. More like an angel than a human. She’d been in her high school choir before she got me in her belly. Once I asked her why she didn’t join the church choir, but she just said she didn’t want to talk about it. After she finished her song to me each night, she’d remind me to say my prayers to Jesus and leave my door open a crack in case I needed her. Our cat perched on the window and looked out.

One night, after she left, I snuck out of Grandma’s “office,” where I slept, into the hallway. I spied on her through the crack she left in her bedroom door, careful not to make any noise because my grandma was across the hall in her own room, probably reading some book from the dollar bin.

My mother sat in bed, her eyes streaked with the Vaseline she used to take off her make-up. She was sifting through old photographs. I imagined what they might be: Dad hiking on the Olympic Peninsula, Dad drinking a beer outside a tent at Priest Lake, Dad holding me as a baby, so small my cross necklace would have reached the ground.

The next morning while my grandmother was out grocery shopping, the doorbell rang. My mother was in the habit of not answering the door, letting the sound of the bell pass over her body like the gong in meditation. It would end, and whoever it was would leave her with me and the cat and the blank space that used to hold my father. But this time the person at the door did not leave; they kept ringing the bell. Finally, my mother moved to the door. I crept up on the first stair, so the wall would hide me from whoever it was. I peeked out slightly.

“Hello,” said Scarlett, smiling.

There she was on the porch. She stood very straight and tall, as if little strings from the sky were tugging her up. The cross hung from her neck, and she held a plate of green Jell-O with pears. “My name is Scarlett. I live across the street with my husband, Daniel. Your mother told me you were coming to stay here, and I wanted to personally welcome you to the neighborhood. I made you some Jell-O; I hope you like it.” She handed the plate to my mother.

“Thank you,” said my mother, taking the plate much too slowly, her body forming a wall between Scarlett and the inside of the house. I wondered why she couldn’t be more polite and invite her in for cookies. Was it because she was jealous Scarlett still had a husband?

“It’s a pleasure to meet you. I already met your daughter, Saige. I gave her a necklace like mine; I hope you don’t mind. She’s such a sweet girl. Doesn’t talk much, though. Is she very shy?”

Adults always called me shy.

“She’s always been quiet,” said my mother. I thought my mother had always been quiet, too.

“By the way,” Scarlett said, her voice getting faster, “I hope this isn’t too personal of a question, but are you a Christian?”

My mother took me to Holy Spirit Baptist Church every Sunday. My grandma said she had only started going to church when she got pregnant with me, and she made my father go with her, even though he never prayed a day in his life and didn’t even accept Jesus Christ as his Lord and Savior.

A leaf drifted down from the sky and landed on Scarlett’s shoulder. She brushed it off, twitching her nose a bit.

“Yes, I’m a Christian,” said my mother.

“Oh, good. I am so happy for you.” Scarlett’s face filled with a bit more color. “You see, I run a Bible study for the children in the neighborhood. I’ve been doing it since Daniel and I got married and moved here three years ago. The children come over once a week, and we sing songs and recite verses, and I teach Bible stories. It’s so good for the children to get to know each other and to share God’s love. I would be thrilled to invite Saige to join, if it’s okay with you.”

I clenched my teeth.

My mother crossed her arms, gripping her sweater closer around her. “That’s very kind of you, but I don’t know…we go to a Baptist church, and I like that, but there are so many different denominations. I’m not sure if I want her learning about God when I can’t see what she’s learning.”

Scarlett didn’t respond right away.

My mother said, “Just, you know, I don’t want to confuse her. Things are so complicated as is.”

The color in Scarlett’s face faded slightly. “Oh, okay…Of course, I understand,” she said. “Things are very complicated. Well, if you change your mind, you know where to find me. The invitation is always there. Your mom told me about your situation, you know. I’m sure it’s all very hard on Saige. It might help her to have some activities.” Her eyes moved in my direction. I pulled my face back right away, hiding it completely behind the wall. She knew I was here. I wondered if it was because she snuck around too, spying on people and hiding in corners.

“Nice to have met you,” my mother managed to say. Scarlett, I’m sure, smiled before turning away down the steps. The door shut, and I scurried up the stairs and into Grandma’s office/my room.

I thought all day about the Bible study. I set up the stuffed animals Grandma gave me on the futon, draping the cross necklace around my biggest bear, and taught them about God. I tried to explain everything.

“A long time ago,” I said, “God made everything, bears and people and flowers, and it was all beautiful. He lives in Heaven in the sky, I think floating around on clouds all the time. He made Heaven too. Everything was perfect, but there was an angel Lucifer who wanted to be bad, so he left Heaven and created Hell. Even though Lucifer lives in Hell, which is underground, he is always coming to Earth and filling it up with evil and temptation.”

The animals looked worried.

“But don’t worry!” I said. “You can escape Lucifer and his evil friends. The only way is to trust Jesus Christ, that’s God’s son, as your savior, because He is full of love and wants the best for us.”

One of the bears asked why we should trust Jesus, not God, when God is the one who made everything in the first place.

“They’re the same person,” I said, “and there is also the Holy Ghost. He’s part of it too.”

The bear wanted to know how three things could be one thing. The rabbit wanted to know if you dug a deep enough hole, would you get to Hell. I decided there was much more work for me to do before I could go on teaching. My mom never wanted to answer my questions, but I was sure Scarlett would.

Scarlett spoke a sweet way to my mother. She loved us both, I was almost sure of it. Why had my mother said no to her? Was it because she figured anyone who lived in that house must be evil?

The next morning, Oscar was staring out my window at something. He always discovered the most interesting things. I looked out with a pair of binoculars my father had left behind. I adopted them as my favorite toy; with them I saw far away from the place I lived. On the sidewalk outside Scarlett’s house, there was a white bucket with flowers sticking out of it. I ran down the stairs right away and, still in my pajamas, out the door and across the street. There were twelve flowers sticking out of the bucket, all different kinds: a tulip, a daffodil,

a rose. There was a sign on the bucket that said “Flowers: 25 cents. Please be honest. God is watching.” I looked around. No sign of anyone who could have put it here. I was touching the petals of the red tulip when I heard Scarlett.

“Good morning, Saige,” she said. She startled me. Where did she come from? “What a pretty nightgown. What have you found there?”

I quickly took my hand off the tulip. She had on a sunhat over her braid today, with the widest brim and the longest ribbon I’d ever seen, like two halos.

“Beautiful flowers for beautiful girls,” she said. “Which is your favorite? I bet it’s that tulip.”

I nodded, not making eye contact.

“I see they cost a quarter. Let me buy it for you,” she said. Scarlett dropped the light silver coin into the bucket. It rattled in the bottom for a moment, and she handed me the tulip.

“Thank you,” I managed to say.

“You’re very welcome,” she said, and patted me on the head. I felt the residue of her fingers there, like a hat of paper, for the rest of the day.

In the living room I stacked up colored blocks, building the tallest tower I could, trying to make it bigger than the piano my grandma bought at a garage sale when my mother was in high school. I hadn’t heard her play since my father left. Like everything that was my mother’s, it sat there, collecting dust.

“Mom, why can’t I go to the Bible study?” I asked.

My mother sighed. “Because, Saige, we go to a Baptist church. I don’t know that lady. I don’t know what kind of church she goes to or what she believes. There are lots of churches: Mormon, Jehovah’s Witness, Liberal Christian. She could believe anything: that we shouldn’t celebrate Christmas, that Jesus was married, that Hell isn’t real, that Noah’s Ark never actually happened. You can’t go; I’m sorry. But you can keep going to Sunday school with me.”

The Paper Garden

The Paper Garden